ساختار بازار و هزینه سرمایه

| کد مقاله | سال انتشار | تعداد صفحات مقاله انگلیسی |

|---|---|---|

| 19852 | 2013 | 8 صفحه PDF |

Publisher : Elsevier - Science Direct (الزویر - ساینس دایرکت)

Journal : Economic Modelling, Volume 31, March 2013, Pages 664–671

چکیده انگلیسی

We contribute to the finance literature in two main ways. First, we present a theoretical capital asset pricing model (CAPM) to price assets in different market structures. Second, we use our model to analyze whether when markets are partially segmented using the local or the global CAPM yields significant errors in the estimation of the cost of capital for a sample of firms from developed and emerging countries.

مقدمه انگلیسی

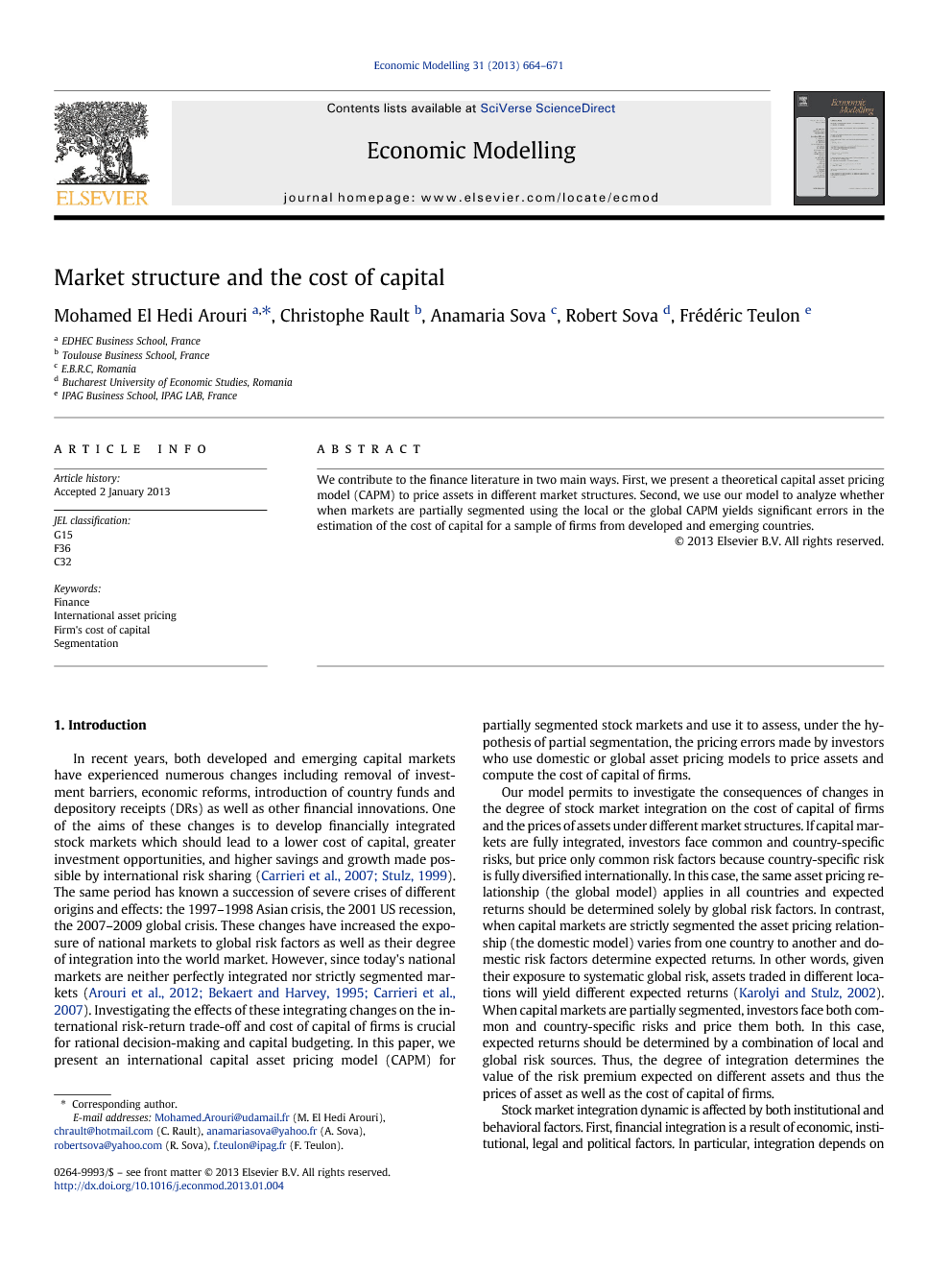

In recent years, both developed and emerging capital markets have experienced numerous changes including removal of investment barriers, economic reforms, introduction of country funds and depository receipts (DRs) as well as other financial innovations. One of the aims of these changes is to develop financially integrated stock markets which should lead to a lower cost of capital, greater investment opportunities, and higher savings and growth made possible by international risk sharing (Carrieri et al., 2007 and Stulz, 1999). The same period has known a succession of severe crises of different origins and effects: the 1997–1998 Asian crisis, the 2001 US recession, the 2007–2009 global crisis. These changes have increased the exposure of national markets to global risk factors as well as their degree of integration into the world market. However, since today's national markets are neither perfectly integrated nor strictly segmented markets (Arouri et al., 2012, Bekaert and Harvey, 1995 and Carrieri et al., 2007). Investigating the effects of these integrating changes on the international risk-return trade-off and cost of capital of firms is crucial for rational decision-making and capital budgeting. In this paper, we present an international capital asset pricing model (CAPM) for partially segmented stock markets and use it to assess, under the hypothesis of partial segmentation, the pricing errors made by investors who use domestic or global asset pricing models to price assets and compute the cost of capital of firms. Our model permits to investigate the consequences of changes in the degree of stock market integration on the cost of capital of firms and the prices of assets under different market structures. If capital markets are fully integrated, investors face common and country-specific risks, but price only common risk factors because country-specific risk is fully diversified internationally. In this case, the same asset pricing relationship (the global model) applies in all countries and expected returns should be determined solely by global risk factors. In contrast, when capital markets are strictly segmented the asset pricing relationship (the domestic model) varies from one country to another and domestic risk factors determine expected returns. In other words, given their exposure to systematic global risk, assets traded in different locations will yield different expected returns (Karolyi and Stulz, 2002). When capital markets are partially segmented, investors face both common and country-specific risks and price them both. In this case, expected returns should be determined by a combination of local and global risk sources. Thus, the degree of integration determines the value of the risk premium expected on different assets and thus the prices of asset as well as the cost of capital of firms. Stock market integration dynamic is affected by both institutional and behavioral factors. First, financial integration is a result of economic, institutional, legal and political factors. In particular, integration depends on the harmonization of stock exchange rules and the ability of foreign investors to access domestic assets as well as the ability of domestic investors to access foreign investment opportunities. In fact, access to worldwide investment opportunities, through direct means and homemade diversification, increases the exposure of domestic assets to global factor and therefore improves the national stock market integration level. However, we should mention that although regional and international harmonization of exchange trading rules encourages greater investor activity, it often allows flexibility in the implementation of clauses and therefore this partially harmonization could create partially integrated markets (Cumming et al., 2011). Second, behavioral factors such as risk aversion, relative optimism, and information perception may also affect the desire to invest abroad and thus market integration. Therefore, even in the absence of institutional barriers to international investments, indirect barriers can still discourage foreign investors and prevent world stock market integration. Thus, the process of stock market integration is complex, gradual and takes years, with occasional reversals and most domestic stock markets should be between the two theoretical extremes of strict segmentation (integration zero) and perfect integration (Bekaert and Harvey, 1995 and Carrieri et al., 2007). Therefore, assessing the degree of market integration can appropriately be addressed only within the context of an international capital asset pricing model. In the recent decades, the finance literature has introduced new theoretical works in the field of risk-return trade-off and asset pricing in different market structures (Bell, 1995). Overall, one can classify the available models in two categories: theoretical domestic asset pricing models in which it is assumed that markets are strictly segmented (Ross, 1976 and Sharpe, 1964 among others) and theoretical international asset pricing models in which it is assumed that markets are perfectly integrated (Adler and Dumas, 1983, Grauer et al., 1976 and Solnik, 1974 among others). However, there are only few theoretical asset pricing models for partially segmented markets, the most known are those developed in the vein of Black (1974) and Errunza and Losq (1985) in which a specific investment barrier is generally introduced and its effects on the equilibrium returns are derived.1 For instance, Black (1974) presents a model of international asset pricing in the case of partially segmented markets. The author develops a two country-model in the presence of explicit barriers to international investment in the form of a tax on holdings of assets in one country by foreigners. This model was extended by Stulz (1981) and Cooper and Kaplanis (2000). The authors show that capital budgeting rules depend largely on the level of taxes that discourage the foreign investors from investing internationally. A more general two-country model is proposed by Errunza and Losq (1985) (EL-85 hereafter). This model enables to characterize the mild segmentation of domestic markets. However, some of its hypotheses are too restrictive. In fact, the authors assume that all domestic assets can be traded by all investors (both domestic and foreign investors), whereas foreign assets are not accessible to domestic investors because of restrictions imposed by the foreign government. EL-85 show that the foreign assets are priced according to the traditional global CAPM, but there is a super risk premium, proportional to the conditional market risk, for the restricted assets. Errunza and Losq (1989) (EL-89 hereafter) extend the EL-85 model to a multicounty framework. However, alike EL-85 the authors reduce segmentation factors to the only effects of capital flow restrictions and thus their model is again built on a simple explicit formalization of segmentation factors. More precisely, they distinguish between two types of securities: securities that can be traded by any investor in the world (the core of the market), and restricted securities (the periphery of the market constituted of N segments such that no investor can trade on more than one segment). No cross-investment between segments in the periphery is allowed and investors in the core are denied access to the periphery segments. Thus, segments (countries) in the periphery are assumed to be completely segmented. The authors establish that in a number of cases, their multi-country model leads to significantly different asset pricing relationships compared to the EL-85 two-country model. In particular, it allows analysis of integrative changes in the world market structure. Nevertheless, stock market integration is a complex and gradual process involving many different kinds of explicit and implicit barriers, and the models discussed above are clearly not flexible enough to investigate the complexities of the market integration. In the absence of an established theoretical model that specifies the continuous economic mechanism moving a market from segmentation to integration, Bekaert and Harvey (1995) propose a purely empirical model of time-varying market integration that allows for the relative importance of global and domestic information on stock returns to change over time. This model is simply an econometric combination of a domestic CAPM and an international one. The integration measure is modeled as a function of national and global variables. An alternative ad-hoc model is developed by Carrieri et al. (2007) who adopt a time-varying version of two-country EL-85 model. The results of the empirical tests confirm the findings of previous works and argue that developed markets are highly integrated in the world market while emerging markets have low integration degrees ( Adler and Qi, 2003 and Hardouvelis et al., 2006). The current paper aims to fill this gap by presenting a model in order to better understand the complex mechanisms that move a national stock market from segmentation to integration and to investigate the effects of this transformation on the cost of capital of firms and on the prices of assets. Instead of imposing restrictions on assets as in all previous models, we hypothesize that there are different types of investors and assume simply that some investors do not want and/or do not have access to foreign assets as a result of explicit and/or implicit barriers on inflows and/or outflows, barriers which may make markets partially segmented. Starting from that, we derive the equilibrium asset pricing relationship and investigate the effects of changing market structures on the prices of assets and the cost of capital of firms. The main theoretical implication of our model is that if investors do not hold all international assets, the world market portfolio is not efficient and the traditional global CAPM must be augmented by a new factor which reflects the proportion of the domestic risk undiversifiable internationally because of segmentation. The more integrated the markets, the greater the decrease in the premium required on this additional risk factor, and the lower the cost of capital. If markets are perfectly integrated, our model converges to the traditional global CAPM. The Fig. 1 illustrates the main issues examined in this paper as well as our contribution to previous works on stock market integration and asset pricing models. The partial integration of national stock markets is the maintained hypothesis and thus asset returns are determined by a combination of local and global risk factors.2 We contribute to the financial literature by presenting a model to directly price assets in that context. A pricing error may arise from an individual firm if the domestic CAPM (which prices directly local risk factors and potentially indirectly global factors through their effects on local factors) or the global CAPM (which prices directly global risk factors and potentially indirectly local factors through their effects on global factors) is used to compute the cost of capital instead of the partially segmented CAPM (which prices directly both local and global risk factors). The size of this pricing error depends on the degree of integration of the studied stock market into the world capital market. We contribute to previous works by assessing these pricing errors for a sample of firms from developed and emerging countries. Indeed, our paper is the first to assess the pricing errors made when markets are partially segmented into the world capital market but investors use domestic or global models to compute the cost of capital of firms (Koedijk et al., 2001; Stulz, 1995). Full-size image (27 K) Fig. 1. Local, global and mixed computation of the cost of capital. Figure options The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we introduce our model and discuss its main implications. Section 3 assesses the pricing errors that arise if the domestic or the global CAPMs are used instead of our model to compute the cost of capital of firms. Concluding remarks and future extensions are in Section 4.

نتیجه گیری انگلیسی

Previous works on cost of capital in intermediate market structures often rely on ad-hoc econometric combinations of global and local risk factors. The findings of these works are rather heterogeneous and mostly inconclusive. In this paper, we first introduce a model to compute equilibrium expected asset returns in partially integrated markets. In contrast to previous works on international asset pricing, our approach is not to look into investors portfolio holdings directly but we simply consider that there are different types of investors' behavior and investigate the consequences of this assumption on international asset pricing and market structure. Specifically, we assume that because of institutional and/or behavioral factors not every investor is willing or able to hold assets from around the world in proportion to market capitalizations and thus to hold the market portfolio. We show that if some investors do not want and/or are unable to hold international assets, the remaining investors will be unable to hold the world market portfolio. After all, the first investors' holdings and the second investors' holdings together make up the entire world market. As the relative per capita supply of the stocks that the first investors hold in limited quantities or simply do not hold is high, the prices of these stocks will be relatively low. Thus, a local risk premium can be rationalized to compensate investors for the excess supply of some stocks. In that context, the traditional global CAPM continues to hold with regard to an altered supply/world market portfolio but it does not hold with regard to the actual world market portfolio. The traditional global CAPM must be augmented by a new risk factor that reflects the part of the country-specific risk undiversifiable internationally because of markets segmentation. The more the markets became integrated, the more the premium required on this additional risk factor decreases and the lower the international cost of capital. Second, we employ our model to assess, under the hypothesis of partial segmentation, the pricing errors made by investors who use the domestic or the global asset pricing model to price assets and compute the cost of capital of firms. We show that the three models (our model, the traditional global CAPM and the domestic CAPM) yield significantly different cost of equity estimates in most cases and that differences between the estimated costs of equity are higher for firms from emerging markets characterized by high level of segmentation. For highly integrated countries, local and global risk factors are often highly correlated and the three models generally lead to close estimations of the cost of capital. There are several avenues to extend our work for future research. First, our model can be extended to include deviations from PPP and investigate how exchange rate risk may affect the cost of capital of firms from emerging and developed countries. Second, the model and empirical approach introduced in this article could be used to assess the effects of regional integration on the cost of capital. Finally, further research could examine the asymmetries in the reactions of firms from emerging and developed countries to recent financial crises as well as the evolution of their cost of capital during periods of instability.