This study examined the construct validity of narcissistic personality disorder (NPD) by examining the relations between NPD and measures of psychologic distress and functional impairment both concurrently and prospectively across 2 samples. In particular, the goal was to address whether NPD typically “meets” criterion C of the DSM-IV definition of Personality Disorder, which requires that the symptoms lead to clinically significant distress or impairment in functioning. Sample 1 (n = 152) was composed of individuals receiving psychiatric treatment, whereas sample 2 (n = 151) was composed of both psychiatric patients (46%) and individuals from the community. Narcissistic personality disorder was linked to ratings of depression, anxiety, and several measures of impairment both concurrently and at 6-month follow-up. However, the relations between NPD and psychologic distress were (a) small, especially in concurrent measurements, and (b) largely mediated by impaired functioning. Narcissistic personality disorder was most strongly related to causing pain and suffering to others, and this relationship was significant even when other Cluster B personality disorders were controlled. These findings suggest that NPD is a maladaptive personality style which primarily causes dysfunction and distress in interpersonal domains. The behavior of narcissistic individuals ultimately leads to problems and distress for the narcissistic individuals and for those with whom they interact.

Introduction

Narcissistic personality disorder (NPD), despite substantial interest from a theoretical perspective, has received very little empirical attention [1]. In fact, some have concluded that “most of the literature regarding patients suffering with NPD is based on clinical experience and theoretical formulations, rather than empirical evidence” [[2], p 303]. A large majority of empirical studies on narcissism come from a social-personality psychology perspective which, although methodologically sophisticated and important, may not pertain to NPD given the reliance on undergraduate samples and the use of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory (NPI) [3]. Trull and McCrae [4] have noted that narcissism measured by the NPI appears to be made up of high Extraversion, low Agreeableness, and low Neuroticism from the Five-Factor Model of personality [5], whereas DSM definitions suggest low Agreeableness, high Neuroticism, and no relation with Extraversion. These authors suggest that “most narcissistic scales do not square well with DSM-III-R criteria for NAR” [ [4], p 53]. The field must be cautious about relying on these studies to inform our knowledge of NPD. The few empirical studies of NPD that have used clinical samples and DSM-based measures have focused on the underlying factor structure and item content [6], [7] and [8]. In particular, there is a striking lack of data regarding the impairment and distress associated with NPD. Central to the issue of validity for any DSM disorder is whether it is actually associated with distress or impairment—in fact criterion C for PD from DSM-IV [ [9], p 689] mandates that one of the 2 be present to make a PD diagnosis. Although there is good evidence for the functional impairment of PDs in general [10] and [11], and certain specific PDs such as borderline [12], schizotypal, and avoidant [13], it is still quite unclear whether NPD predicts psychologic distress and problems in various life domains.

As noted, the association between NPD and psychologic distress is particularly unclear. The DSM-IV suggests that these individuals have a “very fragile” self-esteem (p 714), are “very sensitive to injury from criticism or defeat” (p 715), and that “sustained feelings of shame or humiliation…may be associated with social withdrawal” and “depressed mood” (p 716). However, given the derivation of the DSM over time, these statements appear to be the result of expert opinion rather than empirical findings. Results from clinical samples are both sparse and contradictory. In fact, a meta-analysis of the relations between the FFM and DSM PDs found an effect size (ie, r) of only 0.03 between Narcissism and Neuroticism, which measures emotional stability and the tendency to experience negative affective states such as depression, anxiety, and shame [14]. However, this hides the substantial variability of the findings; of the 18 included effects, 5 were significantly positive, 7 were significantly negative, and 6 were nonsignificant. Within clinical samples, the effect size was 0.14 suggesting a small but significant relation to Neuroticism. There has also been some speculation that narcissism may be linked to higher rates of suicide [2], although the data are quite limited.

Alternatively, Watson et al [15] found significant negative relations between measures of narcissism (derived from the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2 [16]) and depression in 2 clinical samples. Studies on comorbidity between PDs and Axis I disorders have not found a relation between NPD and depression or anxiety-related disorders [17], [18], [19] and [20]. Furthermore, findings from the large nonpsychiatric literature on narcissism conducted from a social-personality perspective suggest a negative relation between narcissism and psychologic distress. Research using the Narcissism Personality Inventory has suggested that narcissistic individuals are psychologically resilient, relatively immune to psychopathology, and manifest primarily interpersonal impairment [21] and [22]. Indeed, a reading of the social personality might lead one to conclude that narcissism, as a result of being composed of high positive and low negative affect and high self-esteem, is an adaptive trait [23].

Where the clinical lore and social-personality data do converge is on the interpersonal impairment linked with narcissism. The DSM-IV postulates that “interpersonal relations are typically impaired due to problems derived from entitlement, the need for admiration, and the relative disregard for the sensitivities of others” (p 716). Empirical studies of narcissism in the social-personality literature find that it predicts a self-centered, selfish, and exploitative approach to interpersonal relationships, including game-playing, infidelity, a lack of empathy, and even violence [24] and [25]. The negative consequences of narcissism are felt especially strongly by those who are involved with the narcissist [26]. How quickly this personality style manifests this interpersonal impairment is up for debate. There is some evidence that the interpersonal difficulties associated with narcissism are only apparent over time, with narcissism being associated with apparently positive interpersonal functioning during initial relationship stages [27] and [28]. However, other studies have found that individuals with unrealistically high positive self-evaluations are rated negatively by independent raters after a very brief competitive interaction with a peer [29]. Unfortunately, there are very few data on NPD and interpersonal impairment using clinical samples. There are data from therapeutic relationships where items from a measure of countertransference were rated by a sample of psychiatrists and psychologists for patients with NPD. The authors of this study found that “clinicians reported feeling anger, resentment, and dread in working with patients with NPD; feeling devalued and criticized by the patient; and finding themselves distracted, avoidant, and wishing to terminate the treatment” [ [30], p 894]. These findings provide strong support for the interpersonal impairment these individuals experience as even trained clinicians experience strong negative feelings about these types of clients.

Given the relatively stronger evidence of a link between NPD and interpersonal impairment than between NPD and psychologic distress, it is plausible that NPD, at times, leads to clinically significant depression and/or anxiety, but these negative affective states are probably secondary to the interpersonal impairment. That is, NPD may lead individuals to experience failure in a number of important domains (eg, romance) that might lead to psychologic distress; however, this distress may not be endemic to NPD. This may differ from other PDs such as borderline in which negative affectivity appears to be an intrinsic part of the disorder.

The goals of the current study are as follows: (1) To assess the association between NPD and psychologic distress including depression and anxiety. (2) To assess the association between NPD and impairment, including indices of romantic, social, occupational, and general impairment, as well as the spillover effects of NPD on significant others. (3) To assess the predictive power of NPD in relation to psychologic distress and impairment over a 6-month period. (4) To test a model in which any positive link between narcissism and psychologic distress is accounted for by impairment. (5) To assess the unique predictive power of NPD in predicting psychopathology and impairment, when controlling for the other Cluster B personality disorders.

3. Results

3.1. Capturing narcissism: concurrent and longitudinal relations

3.1.1. Sex differences

There were significant sex differences for narcissism in sample 1 [t(150) = 4.14, P < .001] and sample 2 [t(149) = 1.98, P < .05], such that men had higher NPD symptom counts. All correlations presented in Table 2 were tested separately for men and women; no significant differences were found.

Table 2.

Characterizing NPD: relations with Axis I psychopathology and impairment

Mean SD NPD Symptoms—Sample 1 (r) Mean SD NPD Symptoms—Sample 2 (r) wr

Distress/psychopathology (concurrent)

Depression (HAM-D) 14.4 7.9 0.05 10.93 7.5 0.18⁎ 0.12⁎

Anxiety (HAM-A) 15.0 8.8 −0.01 11.85 8.2 0.24⁎⁎ 0.11⁎

Distress/psychopathology (longitudinal)

Depression (HAM-D) 7.86 6.6 0.15 8.33 7.1 0.26⁎⁎ 0.21⁎⁎

Anxiety (HAM-A) 8.55 7.5 0.20⁎ 9.08 7.4 0.25⁎⁎ 0.23⁎⁎

Impairment (concurrent)

GAF scores 54.6 7.2 −0.12 61.73 11.5 −0.26⁎⁎ −0.19⁎⁎

Overall impairment 3.22 0.67 0.44⁎⁎ 2.71 0.83 0.34⁎⁎ 0.39⁎⁎

Social 2.85 0.88 0.37⁎⁎ 2.77 0.88 0.16⁎ 0.27⁎⁎

Romantic 3.70 0.72 0.22⁎⁎ 3.14 0.91 0.23⁎⁎ 0.22⁎⁎

Work 2.86 0.94 0.36⁎⁎ 2.36 0.98 0.27⁎⁎ 0.32⁎⁎

Distress—in a significant other 3.01 0.67 0.42⁎⁎ 2.38 0.89 0.50⁎⁎ 0.46⁎⁎

Impairment (6 mo)

GAF scores 62.20 8.5 −0.20⁎ 62.00 11.51 −0.30⁎⁎ −0.26⁎⁎

Overall impairment 3.24 0.71 0.43⁎⁎ 2.81 .85 0.35⁎⁎ 0.39⁎⁎

Social 2.91 0.87 0.33⁎⁎ 2.85 .90 0.17⁎ 0.24⁎⁎

Romantic 3.63 0.84 0.27⁎⁎ 3.21 .88 0.24⁎⁎ 0.25⁎⁎

Work 2.96 0.95 0.24⁎ 2.48 .99 0.31⁎⁎ 0.28⁎⁎

Distress—in a significant other 3.03 0.80 0.42⁎⁎ 2.51 .94 0.52⁎⁎ 0.48⁎⁎

wr indicates weighted mean effect size.

⁎

P ≤ .05.

⁎⁎

P ≤ .01.

Table options

3.1.2. Relations with psychologic distress and impairment: concurrent and longitudinal findings

Concurrently, narcissism was related to ratings of depression and anxiety only in sample 2 (see Table 2). Longitudinally, narcissism was related to time 2 depression in sample 2 and anxiety in both samples. The weighted effects sizes (taking into account the correlations from both samples and weighting them on the basis of sample sizes) were small in all cases.

The pattern of findings between narcissism and impairment was quite consistent across assessments and samples. Narcissistic personality disorder symptoms were related to lower GAF scores in 3 of 4 instances. In addition, NPD symptoms were related to overall impairment, as well as all specific indices of impairment including impairment in romance, work, social life, and causing distress to significant others. Of the specific impairment scores, “distress to significant others” demonstrated the largest weighted effect sizes (r's = 0.46 and 0.48).

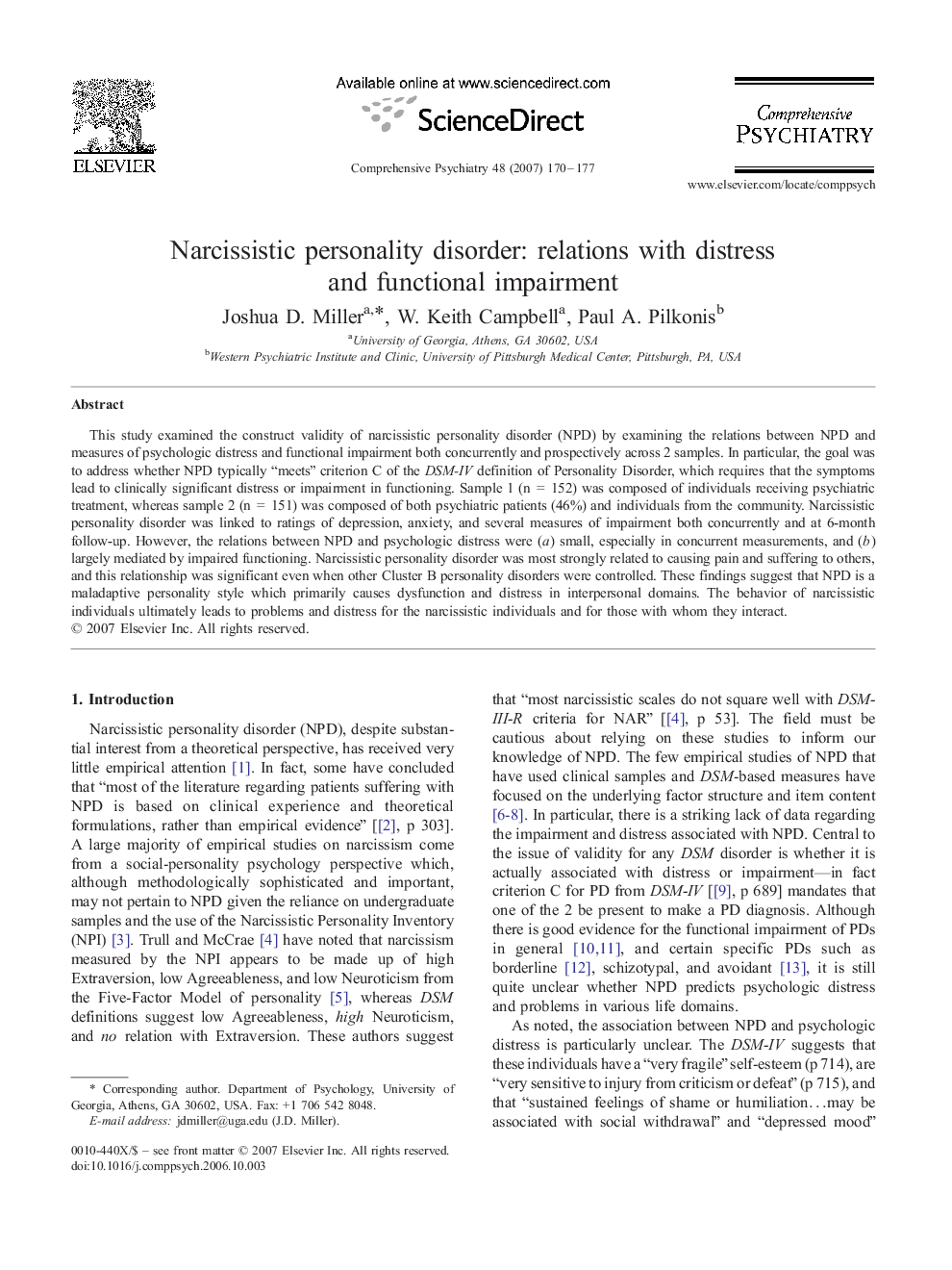

3.1.3. Impairment as a mediator of the relationship between narcissism and psychologic distress

We next examined the hypothesis that narcissism may be related to psychologic distress primarily due to the impairment it causes in various life domains (see Fig. 1). To examine this, we conducted a series of regression analyses. First, we regressed time 2 distress (eg, depression, anxiety, GAF) on time 1 narcissism. Next, we regressed the mediator (time 2 overall impairment) on time 1 narcissism. Finally, we regressed time 2 distress variables on time 2 impairment and time 1 narcissism. These path analyses test whether functional impairment mediates the relations between narcissism and later distress. In addition, Sobel tests (which yield a z score) were used to test for statistical mediation. In sample 1, there was significant mediation by impairment for the relation between NPD and time 2 depression (z = 2.81, P < .01) and time 2 GAF scores (z = 4.14, P < .01). In addition, there was a trend toward significant mediation (z = 1.81, P < .07) for the relation between NPD and time 2 anxiety. In sample 2, the relations between NPD symptoms and depression, anxiety, and GAF scores were all significantly mediated (z's = 3.31, 3.26, and 3.59, P < .001, respectively) by the impairment rating. Across these mediation models, the direct effect of narcissism on psychopathology decreased significantly after impairment was included in the model; in all 6 cases, narcissism was no longer significantly related to the distress outcome once impairment was included. In fact, the direct effect of narcissism was reduced by between 40% (anxiety, sample 1) and 100% (depression, sample 1; GAF, sample 1; depression, sample 2).

Mediation of the relation between NPD and psychologic distress. tP ≤ .07 *P ≤ ...

Fig. 1.

Mediation of the relation between NPD and psychologic distress. tP ≤ .07 *P ≤ .05, **P ≤ .01. Direct effects of narcissism on outcome variables are noted within the parentheses.

Figure options

3.1.4. Replicating mediation analyses with self-reported PDQ narcissism scores

To reduce concern that the previous results might be due, in part, to common method variance (ie, consensus rating of both predictor and outcome variables), we replicated the same aforementioned model in sample 2 but used self-reported symptoms of narcissism (ie, PDQ) in place of consensus ratings of NPD. The results were nearly identical. Again, Sobel tests were used to test for statistical mediation. There was significant mediation by impairment for the relations between PDQ NPD and time 2 depression (z = 2.78, P < .01), time 2 anxiety (z = 2.70, P < .01), and time 2 GAF scores (z = 2.93, P < .01). The direct effect of narcissism was reduced by between 45% (anxiety) to 70% (GAF).

3.1.5. Narcissism: unique predictive relations of 6-month outcomes controlling for cluster B PDs

Finally, we examined whether narcissism was a unique predictor of psychopathology and impairment once we controlled for the symptoms of antisocial, borderline, and histrionic PDs (see Table 3). This is an extremely conservative test because it requires narcissism to predict above and beyond PDs that are significantly related to NPD (across both current samples, NPD was significantly related to antisocial, borderline, and histrionic PDs; median r = .40) and that might be associated with more serious psychopathology. We conducted a series of regression analyses in which sex, antisocial, borderline, and histrionic PD symptom counts were entered at step 1, followed by NPD symptoms at step 2. As can be seen in Table 3, narcissism was not a unique significant predictor of depression or anxiety at 6-month follow-up, although there was a trend for narcissism predicting anxiety in sample 1. Importantly, of the impairment indices tested, narcissism was a consistent significant unique predictor for only one form of impairment—causing distress to significant others. This pattern was found in both samples. There was also a trend for narcissism predicting romantic impairment in sample 1.

Table 3.

Unique predictive relations across 6 months: narcissism and psychopathology

Depression Anxiety GAF Social Romantic Work Distress to others

Sample 1, β

Step 1

Sex .07 .08 .08 −.27⁎⁎ −.04 −.18⁎ .01

Antisocial −.16 −.06 −.02 .03 −.03 .12 .10

Borderline .36⁎⁎ .17 −.42⁎⁎ .50⁎⁎ .48⁎⁎ .45⁎⁎ .44⁎⁎

Histrionic .02 .09 .09 −.14 −.08 −.11 .16

R2 .12⁎ .06 .16⁎⁎ .30⁎⁎ .19⁎⁎ .26⁎⁎ .35⁎⁎

Step 2

Narcissism .13 .27a −.09 .19 .24a .04 .26⁎

ΔR2 .00 .04a .00 .02 .03a .00 .03⁎

Sample 2, β

Step 1

Sex −.06 .02 .00 −.02 −.11 −.12 −.02

Antisocial −.05 .05 −.08 .08 −.01 .29⁎⁎ .15

Borderline .52⁎⁎ .39⁎⁎ −.52⁎⁎ .35⁎⁎ .43⁎⁎ .40⁎⁎ .41⁎⁎

Histrionic .14 .22⁎⁎ −.12 .02 .19⁎ .08 .33⁎⁎

R2 .31⁎⁎ .30⁎⁎ .39⁎⁎ .16⁎⁎ .28⁎⁎ .42⁎⁎ .51⁎⁎

Step 2

Narcissism .05 .02 −.04 .03 −.04 .02 .23⁎⁎

ΔR2 .00 .00 .00 .00 .00 .00 .03⁎⁎

a

P ≤ .10.

⁎

P ≤ .05.

⁎⁎

P ≤ .01.