ترکیب زمان غیربازاری در تجزیه و تحلیل سود - هزینه برنامه های اجتماعی: کاربرد برای پروژه خود کفایی

| کد مقاله | سال انتشار | تعداد صفحات مقاله انگلیسی |

|---|---|---|

| 23367 | 2008 | 29 صفحه PDF |

Publisher : Elsevier - Science Direct (الزویر - ساینس دایرکت)

Journal : Journal of Public Economics, Volume 92, Issues 3–4, April 2008, Pages 766–794

چکیده انگلیسی

Benefit–cost analysis is used extensively in the evaluation of social programs. Often, the success or failure of these programs is judged on the basis of whether the calculated net benefits to society are positive or negative. Almost all existing benefit–cost studies of social programs count entire increases in income accruing to participants in a social program as net benefits to society. However, economic theory implies that the conceptually appropriate measure of the impact of a government program on any group of individuals is the net change in their surplus (or economic rent), rather than the net change in their income. For example, if a social program causes increases in income by increasing work hours, then the lost nonmarket time that accompanies these increases has value that needs to be counted as a cost when assessing the merits of that program. In this paper, we develop a methodology for incorporating lost nonmarket time into benefit–cost analyses of social programs. We apply our methodology to the Self-Sufficiency Project (SSP), an experimental welfare-to-work program tested on a pilot basis in two provinces in Canada during the 1990s. We find that if losses in nonmarket time are ignored, SSP yields a substantial positive net benefit to society. However, if losses in nonmarket time are taken into account, the net societal benefits are greatly reduced, even becoming negative in certain instances. We conclude that future benefit–cost analyses of social programs must take effects on nonmarket time into account in order to give a more accurate picture of the net benefits of the program.

مقدمه انگلیسی

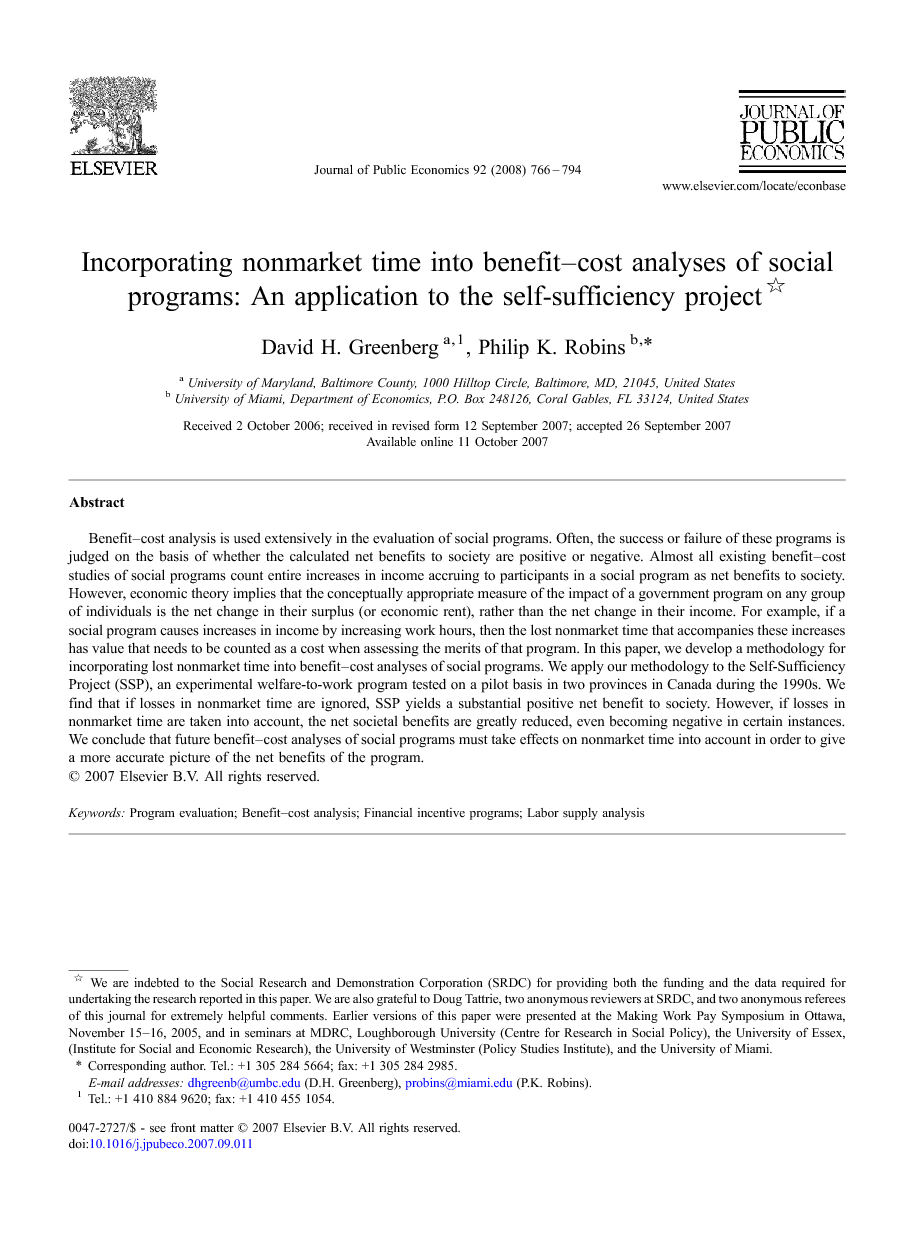

Benefit–cost analysis is used extensively in the evaluation of social programs.2 Often, the success or failure of these programs is judged on the basis of whether calculated net benefits to society are positive or negative. Almost all existing benefit–cost studies of social programs count entire increases in income accruing to participants in a social program as net benefits to society.3 However, economic theory implies that the conceptually appropriate measure of the impact of a government program on any group of individuals is the net change in their surplus (or economic rent), rather than the net change in their income. For example, if a social program causes increases in income by increasing work hours, then the lost nonmarket time that accompanies increases in work hours has value that needs to be counted as a cost when assessing the merits of that program. The basic concept is illustrated in Fig. 1, where curve S is the labor supply schedule of an individual who has successfully participated in a program that increased the person's market wage from Wn to W⁎. As a result of the wage increase, the individual increases hours of work from hn to h⁎. In the diagram, area A represents the increase in both participant surplus and earnings that would have resulted from the wage increase even if the participant had not increased hours of work. Area B represents an additional increase in both participant surplus and earnings, one resulting from the increase in hours that actually takes place. Finally, area C represents a further increase in earnings that results from the hours' increase. However, this last increase in earnings is fully offset by the individual's loss of nonmarket time. Hence, no change in participant surplus is associated with it. Consequently, although areas A, B, and C are counted as benefits when using the net income change measure of program effects, only A and B, the areas above the labor supply curve, are counted in the conceptually more correct net surplus change measure. As will be seen, this simple model can be readily adapted to many types of programs that increase hours of work, including programs that find jobs for the unemployed and programs that provide financial incentives to work, although some modifications to the simple model are necessary. Full-size image (13 K) Fig. 1. Value of lost nonmarket time for a participant in an education or training program. Figure options In this paper, we develop an empirical methodology for incorporating lost nonmarket time into benefit–cost analyses of social programs. We know of only two previous studies that have attempted to adjust estimates of the net benefits of social programs for losses in nonmarket time. Bell and Orr (1994) make some rough adjustments to attempt to account for losses in nonmarket time resulting from a program that increased work hours by providing on-the-job training in health care for welfare recipients. Greenberg (1997) attempts to adjust four previously completed benefit–cost analyses of welfare-to-work programs that did not take account of losses in nonmarket time resulting from the programs. Both studies find that adjusting for lost nonmarket time substantially reduces estimates of the net benefits of the programs they examined. However, Greenberg (1997) finds that this effect is mitigated for programs that increase hours as a result of augmenting human capital, rather than through other means such as job search or financial incentives. Our methodology builds on the basic framework of Greenberg (1997), who shows how to estimate lost nonmarket time for mandatory welfare-to-work programs that attempt to increase employment through various combinations of job search services, work experience, and training services. Our extension estimates the value of lost nonmarket time for voluntary programs that increase employment through financial incentives. Our approach differs methodologically from that of Greenberg (1997) in that our estimated losses in nonmarket time are calculated at the individual level, whereas Greenberg estimates such losses at the aggregate level. Because we focus on individuals, our approach in principle should be more accurate. To derive estimated losses at the individual level, our methodology uses micro-data and statistical matching methods to identify responders to financial incentive programs. We apply our methodology to the Self-Sufficiency Project (SSP), an experimental welfare-to-work program tested on a pilot basis in two provinces in Canada during the 1990s.4 We find that if losses in nonmarket time are ignored, SSP yields a substantial positive net benefit to society. However, if losses in nonmarket time are taken into account, the net societal benefits are greatly reduced, even becoming negative in certain instances. We conclude that future benefit–cost analyses of social programs must take effects on nonmarket time into account in order to give a more accurate picture of the net benefits of the program. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. In the next section, we describe the SSP program and the benefit–cost analysis that was performed as part of the official evaluation of the program. Following this, we discuss why lost nonmarket time is likely to be an important cost of any program like SSP that affects participants' income. Then, we describe how losses in nonmarket time can be taken into account in a straightforward fashion. After taking these losses into account, we reassess the original benefit–cost analysis of SSP. We then examine the sensitivity of our findings to several of the assumptions underlying the benefit–cost reassessment. In an additional section, we compare the methods used in this paper with the somewhat simpler approach used earlier by Greenberg (1997). Finally, we summarize our major findings and draw some implications from them.

نتیجه گیری انگلیسی

The key finding in this paper is that the cost of the nonmarket time lost to persons who responded to the SSP financial incentive was substantial. For example, our baseline estimates, which are based on fairly conservative assumptions, imply that well over a third ($1860 out of $5256) of the gains in income received by the program group was offset by losses in nonmarket time. As a consequence, about three-quarters of the positive net social gains attributed to SSP in the original benefit–cost analysis of long-term IA recipients are eliminated. This baseline finding was subjected to numerous sensitivity tests. All but one of these sensitivity tests produced estimates of SSP's societal effects that are well under $1000 and a few suggest they are negative. The one exception occurs when it is assumed that the labor supply curve has the shape of a backward L and that the reservation wage is at its lower bound. Even in this case, however, SSP's social benefits are estimated to be much lower than those that appear in Michalopoulos et al. (2002). In our view, the backward L labor supply curve is implausible because of its highly discontinuous nature. Thus, we believe that the “true” value of lost nonmarket time is likely to fall somewhere between the estimates based on the elliptical labor supply curve and the estimates based on the linear labor supply curve. The value of the reservation wage is highly uncertain, suggesting that it would be useful in future evaluations of welfare-to-work programs to attempt to obtain its value through carefully conducted surveys. 55 Currently, however, we are only able to determine its lower and upper bounds (respectively, wn and w⁎ for nonworker responders and zero and wn for part-time responders) and conjecture about where in this range it falls. The reservation wage is almost certainly higher than its lower bound value; but it could be even higher than the value at the mid-point of the upper and lower bounds, suggesting that the baseline estimate of $1860 for the cost of lost nonmarket time is probably substantially understated. Thus, we conclude that the cost of the nonmarket time lost to persons who responded to the financial incentives offered by SSP was probably large enough to nearly offset, or even more than offset, the positive net social gains of $2565 that the original benefit–cost analysis attributed to SSP. In assessing this finding, it is very important to keep in mind that we have focused on only one possible limitation of benefit–cost analyses of the sort performed for the SSP evaluation. There are two important additional considerations not taken into account in traditional benefit–cost studies that would act to increase the net gains from a particular program. These are the value that taxpayers place on reductions in the benefit rolls and the effects of the program on the income distribution. Many taxpayers who pay for Income Assistance benefits may feel that recipients of these transfers should be working. SSP did, of course, increase the work effort of IA participants. To the extent taxpayers are willing to pay for such an outcome, this is a benefit of the program that could, perhaps, offset the loss of nonmarket time among those who responded to SSP. No attempt has, however, ever been made to elicit taxpayers' willingness to pay for the substitution of work for transfer payments. Thus, one can currently do little more than conjecture about the size of this benefit. One approach that could be used to obtain information on this topic is contingent valuation, which utilizes surveys to attempt to measure willingness to pay for goods not exchanged in markets. 56 As shown in Table 3, SSP resulted in net gains for the program group, but net losses to the government budget. In other words, there was a transfer of income between program participants and taxpayers. However, in the SSP benefit–cost analysis, the dollars gained by participants were valued the same as those lost by taxpayers. Because participants in SSP had much lower incomes than taxpayers, on average, their marginal utility of income was likely to have been higher. A considerable literature exists suggesting that this difference in marginal utility should be dealt with in benefit–cost analysis by giving each dollar of gain by relatively low-income persons greater weight than each dollar of losses by relatively high-income persons (see Boardman et al., 2005, Chapter 18). If such adjustments were made, then the estimated social net gains from SSP would obviously increase. However, the appropriate weights are unknown. Although contingent valuation might be one way of estimating the weights, to our knowledge it has never been used for this purpose. By demonstrating that the SSP benefit–cost findings look very different when lost nonmarket time is taken into account than when it is not, this paper has two important methodological implications and one important policy implication. The first, and more general, methodological implication is that any benefit–cost analysis that measures benefits as changes in income, rather than as changes in surplus, is likely to be subject to substantial bias. There is one whole area of evaluation studies that almost always uses income changes to measure benefits—benefit–cost studies of education, training, employment, work incentive, and other programs intended to increase earnings—but changes in income are also sometimes used in benefit–cost analyses in other areas (e.g., water resource projects). Of course, changes in income are often more readily obtained than estimated changes in surplus. The second key methodological implication, which follows from the first, is that more work is needed to overcome the limitations of benefit–cost analyses of programs targeted at the disadvantaged (such as training programs, welfare-to-work programs, and income transfer programs) if they are to provide a reliable indicator of program efficacy. Some of these are mentioned above—for example, research on reservation wages, program general equilibrium effects, the relative value of dollars gained (or lost) by low- and high-income persons, and the willingness of taxpayers to pay for increases in the work effort of transfer recipients. The policy lesson follows directly from the methodological implications. Because they do not treat potentially important issues, benefit–cost studies of programs targeted at the disadvantaged produce suggestive, but not fully reliable, findings Although the evaluators conducting benefit–cost analyses are usually careful to point out at least some of their limitations—the SSP analysts certainly were (see Michalopoulos et al., 2002)—the caveats tend to be forgotten by users of the findings and the numbers that are actually produced are stressed in assessing whether the program was cost-effective. Thus, in determining whether the program was successful, policy makers look at whether the program's estimated net benefit (i.e., whether estimated benefits exceed estimated costs), regardless of whether this “bottom-line” figure might be overturned if factors that were left out of the analysis (e.g., the value of nonmarket time) were taken into account. It is important that, until benefit–cost analyses of programs targeted at the disadvantaged become more reliable, policy makers recognize their limitations and treat their findings with great care.